Your art will live on. A call across time and space. Honour the sacredness of how we remind one another that we existed across time.

— Maria Buffalo, as read by Jessie Loyer in nanekawâsis (2024)

There are empty spaces that must be respected—those often long periods when a person can’t see the pictures or find the words and needs to be left alone.

— Tove Jansson, Fair Play (1989)

indian is an idea / some people have / of themselves

dyke is an idea some women / have of themselves— Some Like Indians Endure, Paula Gunn Allen (1988)

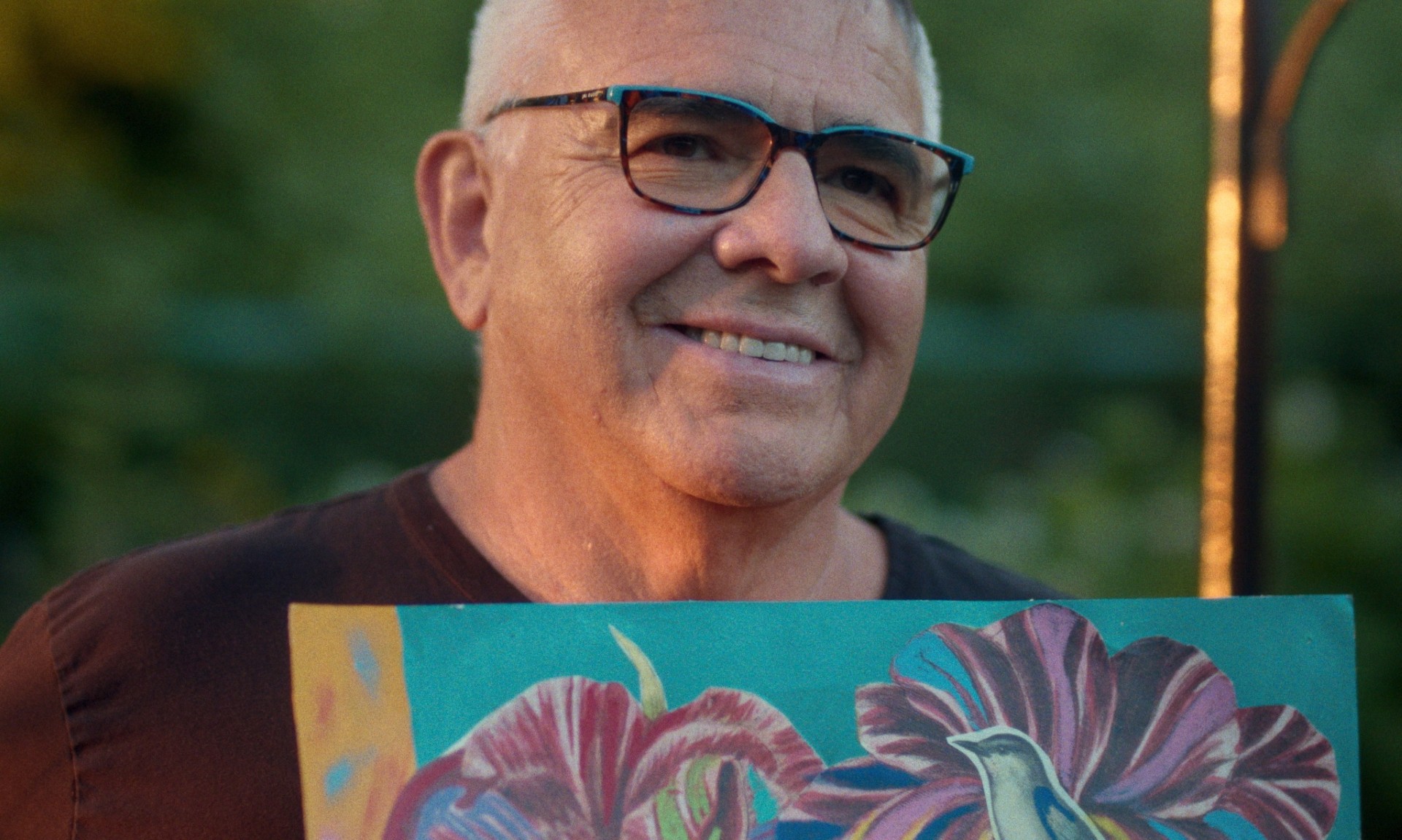

Métis filmmaker Conor McNally has been meticulously working on his documentary feature debut nanekawâsis—about the life and work of Cree painter George Littlechild—for years. Despite being a widely respected Plains Cree artist for decades, I was surprised to learn that Littlechild’s work has not been collected by the National Gallery of Canada, and that he doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. At this pivotal moment in Littlechild’s long and storied career, McNally’s film plays a crucial role in commemorating Littlechild’s legacy. With its focus on the relationships that shape Littlechild’s work—such as his longtime love for his partner—nanekawâsis tells a story of enduring queer love in an Indigenous apocalypse.

Queer love in the apocalypse has become a literary and visual trope in recent years. Amid apocalyptic realities—such as widespread disease and environmental crises—conservative social policies targeting 2LGBTQ+ people have started to permeate everyday discourse. Representations of queer love “at the end” have emerged in response.

At first glance, these representations might seem like expressions of endurance: We’re here, we’re queer, in any mode or reality known on Earth, and to queered peoples. Yet, fetishistic themes of disability and death mar these narratives, hindering any possibility of queer futurity (however ironic such a proposal may be). Amidst a sea of narratives exploring queer deviance and death, nanekawâsis stands out as a realized future, and a remarkable and unexpected memorialization of minor histories and quiet archives.

—

“Long, Long Time,” an episode from the apocalyptic thriller series The Last of Us, stands out amid the trend of narratives depicting apparent queer futurity. The terms “queer” and “future” are, theoretically speaking, an ironic pairing—a tension that becomes evident in the depiction of queer love in apocalyptic media.

The episode tells the story of Bill, whom main characters Joel and Ellie intend to visit but find dead. In a flashback, we learn about the life and death of Bill and his lover Frank, all unfolding amid the turmoil of an apocalypse. Bill is an avid doomsday prepper and survivalist. Titillated to be left alone with his supplies after a strange infection breaks out and changes the world as he once knew it, Bill does everything he can to protect himself from intruders—both undead and alive.

One day, while Bill is working in his garage, Frank gets caught in one of Bill’s traps. Initially overly cautious, Bill attempts to keep Frank at a distance and hopes to send him away quickly, seemingly a trauma response developed long before the fallout. With his quick wit and kind demeanor, Frank eventually convinces Bill to let him into his home, where they share a meal, a kiss, and, eventually, a life.

Bill opens up to Frank, who convinces Bill to take pride in their surroundings and befriend a community of survivors. “It’s how we show love,” Frank says. Frank grows strawberries for Bill, and they enjoy them together under the sun’s rays, giggling. Each moment contributes to a queer love that lasts both their lifetimes. Bill and Frank nurture their love while also creating a loving community around them, bringing together what little beauty and kindness remain.

Yet, lingering death marks their life with discomforting metaphors that mirror those ascribed to gay men during the 1980s and 1990s, when they were dying from AIDS due to systemic neglect within the government and US health systems. “I was never afraid before you showed up,” Bill tells Frank. When the world is already lonely and without love, when you’ve experienced social death, love can represent a future—and with it, the risk of loss that coincides with its potential.

Raiders come across their compound at night, resulting in an explosive gunfight where Bill gets shot. Violence constantly mars the world around them, despite the happy home they have created. Yet, it’s a disease that ultimately separates them. Frank develops a degenerative neuromuscular disorder. Bill spends their later years caring for him after a long life together. Eventually, Frank decides he wants to pass on. One morning, he wakes and tells Bill, “This is my last day.” The two spend one final day together, after which Bill decides to take his own life alongside Frank.

Even the Linda Ronstadt song that lends its name to the episode, playing as we see the pair for the last time, lying dead together in the bed they shared, reinforces a sense of finality and death that underlies their enduring love. Their story ends with a grief-filled tone, resonating with unfulfilled desires cut short by disease and the uncertainty of death. “Cause I’ve done everything I know / To try and make you mine / And I think I’m gonna love you / For a long long time.”

In an era where conservative notions about 2LGBTQ+ communities are shaping public opinion, it’s more important than ever that our love transcends our deaths. When it comes to memory-making, culture, and heritage—yes, I am a positivist and believe that community is possible, having witnessed a community like the one depicted in nanekawâsis—we can embody something beyond the slow degradation of the body due to the emotional toll of social death on queered bodies, spirits, and minds.

About 20 minutes into nanekawâsis, Littlechild’s longtime partner, John, is introduced. McNally portrays their love without sensationalism. Their love is a long love. Littlechild remembers he first visited John’s coastal Indigenous community 31 years ago. Their love is comfortable, like a well-worn sweater. John makes Littlechild laugh by showing him a video of Mildred Gooch as they drive along the highway. While enjoying a walk through the forest, John’s playful spirit shines through when he teases Littlechild about his height. nanekawâsis marks the first public acknowledgment of Littlechild’s identity as a Two-Spirit man and celebrates the love that has shaped his world over the last three decades.

John compares his controlled approach to making art, but describes how Littlechild “feels out his work.” “George is more conservative in his everyday life. I’m [the] opposite … I govern myself through art. George finds freedom.” The artistic freedom that Littlechild experiences, as described by his closest love, is different from the secrecy and isolation he endured in his queered life during the 1980s and 1990s.

Why must the queer always be characterized by yearning, never fully realized, and always self-annihilating? More importantly, how can we transcend this postmodern construct that continually consumes us?

Littlechild’s painting Rainbow Man, Warrior (2011) reflects on the reasoning historical moments like the Stonewall Riots. “People were living in hiding,” says Littlechild, describing a “shame-based” existence. “When I was young, you were always hiding. Places you would meet and gather—it was all clandestine. There was a buzzer to get in or a password. You couldn’t just walk in because you were afraid. You watched how you talked and walked for fear of being outed and the shame.” Littlechild describes hiding his identity as a gay man in a homophobic prairie society during his youth as “torture.” Rainbow Man, Warrior honours Two-Spirit peoples and a time when they were openly represented in community and Creation. The painting aims to “reclaim, heal, and announce we are here.”

Continuing to fetishize the death drive after queered peoples have endured a quiet and systemically condoned generational genocide dishonors their spirit and the lives lost. It reflects a failure to acknowledge that we no longer need to live in secrecy. Red Thought scholars might label such a notion as liberalism. In the teachings of Littlechild, I see it as healing and harm reduction in a world where justice, at times, seems unreachable. It represents a livable reality after an Indigenous apocalypse.

Why must we always be dying, even when we are living? Why is illness leading to death our curse? Disability becomes a negative label applied to the interpretations and portrayals of 2LGBTQ+ lives indefinitely. The irony of queer yearning meeting queer modernity, though romanticized, suggests that culturally, gay and sapphic communities should—and indeed have—moved beyond longing and death. Why must the queer always be characterized by yearning, never fully realized, and always self-annihilating? More importantly, how can we transcend this postmodern construct that continually consumes us?

—

Queer yearning, followed by lesbian death, drives the narrative of the Black Mirror episode “San Junipero.” The audience first meets the main character, Yorkie, in 1987 at a nightclub where she encounters Kelly. Yorkie, a self-described “tourist” in the party town of San Junipero, hesitates as they dance closely, concerned about onlookers. A moment reminiscent of Jane Austen’s romantic tension unfolds when they touch hands but Yorkie retreats into the night without pursuing her attraction to Kelly further.

Yorkie returns to San Junipero a week later to search for Kelly. Kelly drives into the city again in her Jeep, with a dreamcatcher hanging from the mirror. Later that night, the dreamcatcher is visible as Kelly takes Yorkie back to her beach house. Something isn’t right, and the viewer senses anxiety. After Yorkie returns to San Junipero to find Kelly has vanished, she begins to travel through time, eventually locating Kelly in 2002. Kelly had been evading Yorkie and grappling with her anxious attachment.

The viewer discovers that Yorkie is an older woman who fell into a coma at the age of 21 after a car accident that occurred immediately after she came out to her parents. San Junipero is an augmented reality platform that Yorkie accesses once a week. Yorkie has decided to pass over soon. Kelly, also an older woman residing in an assisted living home, has accepted that she will soon die from cancer. Kelly also uses San Junipero weekly as a social outlet.

These women may represent those who couldn’t openly be lesbians in a previous generation. However, illness and disability mark their union in this future. Throughout the final act of the episode, Yorkie tries to convince Kelly to “stay here” in San Junipero after her death. The viewer wonders what Yorkie means. This question is answered at the end of the episode when Yorkie and Kelly’s consciousnesses are uploaded onto servers at a facility named San Junipero. “Heaven Is A Place On Earth” by Belinda Carlisle plays as, after much conflict, Yorkie and Kelly Uhaul forever. As Kelly says during the episode, “Uploaded to the cloud, sounds like heaven.”

The trope of lesbian yearning followed by immediate death after sapphic desire is a common cliché in film and television. In the digital party town of San Junipero, eternal love is death. Even beyond the literal ascent beyond human life needed to achieve sapphic intimacy, lesbian death recurs throughout the episode. Notably, Kelly pulls a Charli XCX and drives recklessly in San Junipero, causing an accident. When Kelly crashes, her body is violently thrown through the windshield, while a dreamcatcher sways wildly in the window.

Is “San Junipero” a reference to Stephen King’s infamous book Dreamcatcher (2001), written under an opioid haze? In the book, an invading alien species unleashes a disease in a community. A group of friends uses the telepathic power they share with a man with Down Syndrome to try to save themselves. Amidst the chaos, an alien called Mr. Gray takes over one of the humans’ minds. The movie ends with the main character realizing that Mr. Gray could only take over his mind because he believed he could—akin to using a dreamcatcher to catch bad dreams. Stephen King frequently uses Indigenous tropes and troubling representations of disability to create so-called horror.

Death and near-death, and what follows, are intrinsically woven with the ideology of Indigenous disappearance in both “San Junipero” and Dreamcatcher, represented by dreamcatchers as metaphors for eternal unrest and the past. This intertwines with notions of disability as deviance in “San Junipero,” “Long, Long Time,” and Dreamcatcher. In Dreamcatcher, a psychic connection between the main characters and a minor character with Down Syndrome makes them susceptible to alien influence. In “San Junipero” and “Long, Long Time,” the social death of Elders in North American societies is referenced, highlighting the neglect and abuse of Elders in poorly funded centres (who were even left alone in centres without care workers at the height of the COVID crisis, in some instances to die alone).

What drives audiences and media makers to repeatedly metaphorically portray the death of Indigenous and gay peoples during historic genocides? The actors and characters change, but analogies for Indigenous and gay disability and death are embedded in the memory-making, heritage, and knowledge about queered peoples in Canadian and American consciousnesses.

The connection between the death drive and Indigenous disability might seem abstract to some. However, Indigenous peoples were foundational to the concept of disability in Canada. In his 2012 paper “Colonialism, Disability, and Possible Lives: The Residential Treatment of Children Whose Parents Survived Indian Residential Schools,” Chris Chapman writes that disability and sickness became defined by measuring the deviance of Indigenous youth and women.

Surveillance of individualized notions of bodily deviance and policing Indigenous health under colonial regimes continues among the children and grandchildren of the individuals who attended Residential Schools. Indigenous Studies scholar and award winning writer Billy-Ray Belcourt argued in his 2018 paper “Meditations on Reserve Life, Biosociality, and the Taste of Non-Sovereignty” that disabilities and sicknesses, such as diabetes, are constructed as deviance from biopolitical markers of health to measure good citizenship. Indigenous communities on reservations are socially constructed as diseased populations, reinforcing disability as a normative mode of Indigenous being (an ouroboros of Indigenous un-health).

McNally animated one [of Littlechild’s paintings] depicting a Native man with long hair who is cumming stars, and the cum-stars become animated spirit themselves.

What I appreciate about Belcourt’s work around the queer is that it is grounded not in auto-ethnography but, instead, Indigenous thought, philosophy, and life writing that could never be reached by the outsider, as Sarah Ahmed has called non-Indigenous anthropologists studying Indigenous peoples. Belcourt, and others working in similar ways, are reshaping what “the humanities” encompass. Belcourt’s work gestures towards futurity, while examining the death drive and the queer, and with ease. His work is not (always) self-annihilating, and never annihilating to other Indigenous peoples who are already marked for death by colonial projects. It recognizes a connection to a tradition of Indigenous life-making older than the queer knowledge that became our words. I see this life drive in Littlechild’s work, too.

Returning to nanekawâsis, a notable presence in the film, if only spirit, was Littlechild’s mother. The film opens with a photo of Littlechild sitting on his mother’s lap. She looks happy. Her eyes are bright. She smiles widely, seemingly so proud to be holding her boy. Littlechild’s mother appears again when an image of Littlechild’s grandmother holding his mother is shown and described.

Despite this mother’s love, what Belcourt might call the biosociality of Native life in Alberta resulted in disease and death for this family. Littlechild’s mother “drank herself into oblivion” and “died on a skid row,” a young Littlechild tells a documentary crew from the 1990s. “Another word for love is mother,” the narrator of nanekawâsis says after this. What is it like to lose your love to a false prophet such as Canada? What is it like to return that love to yourself, to free yourself, through creative modes? I know. Perhaps that’s the difference between NDN thought, as grounded in phenomenological being—which is to say lived experience—and the study of Indigenous peoples.

—

Edmonton River Valley was an important anchor to Littlechild in his early life. The river runs through Edmonton and Littlechild describes it as “polluted” when he was in his youth. In the film, Littlechild returns to his childhood foster home—near the River Valley—and remembers how he started drawing at a young age. By his admission, much of his work deals with “spirit” that he saw in the life around the River Valley. In nanekawâsis, Littlechild represents trauma as strength, as a “gift”—a specific temporality or energy possessed by some, seldomly accurately observed by outsiders, to understand one’s boundaries and own heart. “Color is healing,” Littlechild argues, “Bringing joy into the planet. Coming from where I’ve come from. I’ve seen the dark. I’ve seen the hell. Healing, when you come from a history of colonialism, healing the people and the generations of dysfunction after Residential Schools, loss of control, [and the] government controls your life, it doesn’t allow you to be a people. My ancestors who died wanted to survive and thrive.”

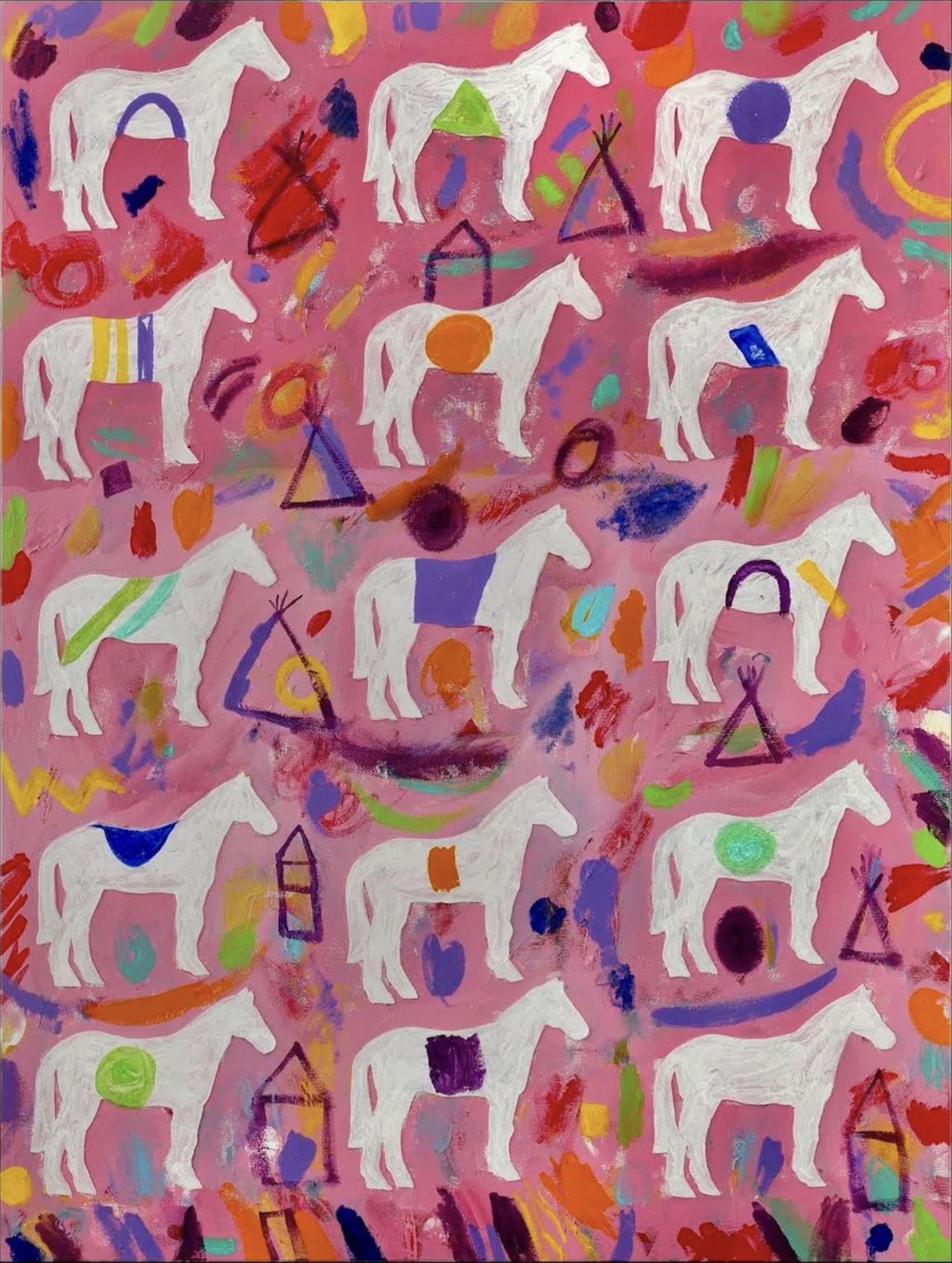

The standout painting at Littlechild’s 2024 exhibition “Ancestral Keepers of the Land, Sky and Horse Spirit” at Ashdale Gallery in Vancouver was “I Honor my horse Spirit.” Littlechild was told by a Cree Elder he has the “spirit of the horse.” Up until that point, horses were always a part of his art practice, and he never understood why until he heard this teaching. The 16 horses in the painting that stand against a backdrop of pink—which matches the color of an Alberta sky at dusk—surrounded by teepees, syllabics, and symbols are a self-portrait of Littlechild through his life. This is the apocalypse and here he/we is/are still.

For many years, Littlechild’s artistic practice included finding photographs of Cree students who had attended Residential Schools in his community. He took those photos to Elders in his community and found those children’s names. Afterward, he created a body of drawings about the children from his community who attended Residential School and died there—who no longer had names. Littlechild says the work was to acknowledge the children and give them a voice. He calls the body of work “a coup” that he could mark on his “coup stick,” referencing a common wartime practice for Cree communities for encountering enemies. In this case, the enemy is Christianity, Canada, and the Residential School system.

McNally breaks the fourth wall several times, appearing interlaced with imagery of Littlechild in a reflection in the mirror, or a reflection in a window. Moments are cut with dialog between McNally and Littlechild remaining so they appear messy or “not clean.” This is very much an intentional visual language. Littlechild is lifted by his community and lifts his community in return. Littlechild’s work is the story of prairie NDN life. Littlechild did survive the loss of love at the (attempted) end of Indigenous life in the prairies, only to witness another community after him.

While “clandestine,” the film makes clear that Littlechild lived a gay life. Littlechild lived in Vancouver for just over half a decade. A montage of photographs and artworks from Littlechild’s life shows a connection to a gay community in Vancouver. So many looks, amazing mustaches, leather, cowboy hats, and hot men on beaches flash on the screen. Littlechild’s art is so gay and represents so much dick. McNally animated one painting depicting a Native man with long hair who is cumming stars, and the cum-stars become animated spirit themselves.

As seen in nanekawâsis, when Littlechild was honoured at a powwow held by his community in 2001, it was John who beaded the vest that Littlechild wore. The vest featured over a million cut glass beads and one of Littlechild’s paintings on the back. At that powwow, Littlechild was given his grandfather’s name nanekawâsis—swift child.

When photos of Littlechild and his partner throughout the years were shown in a montage over sentimental music, I cried in the theatre. I cried some more at home during a re-watch. I felt like a cliché. Then, I thought of Littlechild’s work, and my ancestral responsibility to resist my desire to self-annihilate. I dug deeper and realized—this was the first time I had ever seen a depiction of queer, Native love in the life cycle of an Elder. Though this might not be the case for all NDNs—but is likely the case for many prairie NDNs—this was the first time I had seen, even within my own family, that long, Native love was possible. Native love is possible.