Lauren Crazybull has been quietly developing her painting craft alongside her community for years. An art industry increasingly measuring itself within the metrics of “equity, diversity, and inclusion” has ascribed many labels to Crazybull’s work: Indigenous, feminist, and queer. Art, after all, is defined by its history of objectification, commodification, and labelling of “The Other,” as Crazybull discusses below. Yet, in my recent interview with Crazybull, she constantly defies a simplistic notion of her work as fitting neatly within any identity category. Crazybull refuses a politics of representation and, instead, gestures to art as a means of instilling urban kinship outside of a politics of legibility and recognition. I am reminded of the shifting ideologies of this moment in art history, and am inspired by artists intent on shifting the lens not just in terms of representation, but in terms of structure, as well. While Crazybull does not define her work in terms of identity categories, I describe the movement of artists, writers, and creators Crazybull describes in this interview as the kinship gen. — Jas M. Morgan

Jas Morgan: When I was doing research, I read a few interviews about your work. Obviously representation is something that people like to focus on in your work. For me, there’s something unique about what you represent. Something that goes beyond the typical conversation about Indigenous representation. You represent Two-Spirit folks, feminists, and women, in particular, and pare down those representations (I see this in your choice of muted tones for clothing). Why is that kind of representation important to you?

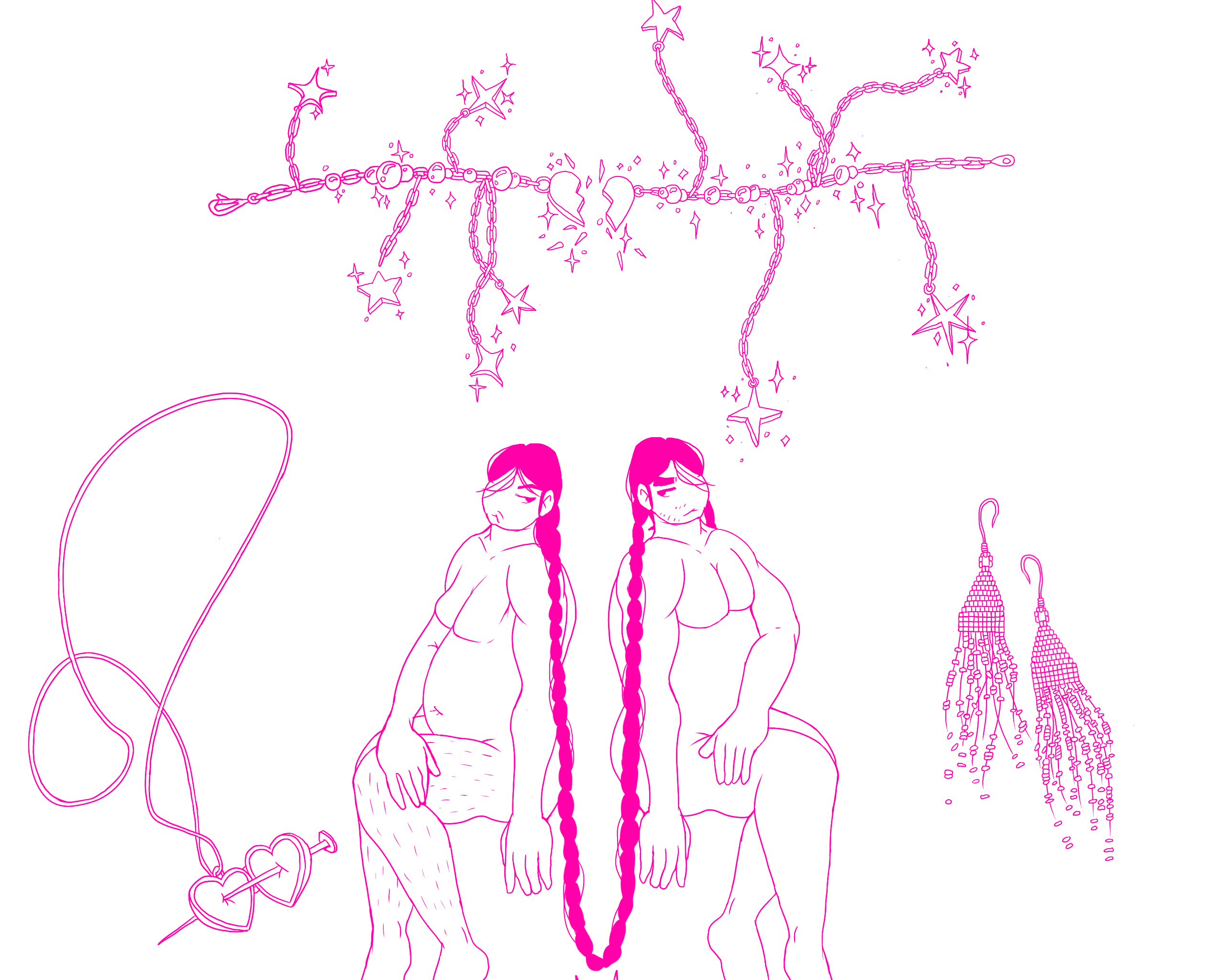

Lauren Crazybull: I have been thinking a lot about presence in my work. I’ve been thinking about Audra Simpson’s essay “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship” and how she talks about Indigenous presence. She talks about land dispossession and how early anthropological works were used to render our voices and make us voiceless or indiscernible. Imperceptible. I’m also looking at the work of this artist, Nicholas Raphael de Grandmaison, who drew these really romanticized drawings of Indigenous people. I’m looking at his work because he drew a lot of Blackfoot people. As a Blackfoot person, I’m interested in thinking about what that work says. It’s really about disappearance. He was sort of positioning himself as, like, his artistic intervention was what was going to keep the memory of us. So it’s about our disappearance and it relied on the fact that we’re going to disappear. When I was thinking about Audra Simpson’s essay, and thinking about de Grandmaison, it got me thinking a lot about what presence would look like. I think that showing people as they are, as they show up to the studio, is a really important part of my work. I don’t want to further romanticize Indigenous people. I want to show other Indigenous folks how I see them and how they’re existing every day. Of course, if they show up and they’re wearing something that signifies—like visual signifiers of Indigeneity—I will include that. Seeing us as we are, as we look day-to-day, like the unremarkable parts of our existence, is important to show presence. For me, I’m very much someone who has not “grown up” around a lot of my own culture. I feel like I’d be doing a disservice if I was trying to make people look extra Native. It wouldn’t be true to me.

JM: How do you build that trust with the people that come in your studio and what does that look like when you’re starting to make a portrait about someone?

It’s hard to define my work because I don’t want it to become a defined thing in the same way as when we look at these anthropological portraits of Indigenous people. Like, I’m presenting a known thing…. I’m rethinking making us so definable and so measured. I’m thinking a lot about that in my work going forward: unknowability.

LC: The relationships are always different and thinking through the ethics of my practice has been important. I’m creating these images of people. I’m thinking about what will happen to the portraits and talking to people about it. But every relationship is different. Sometimes it’s with someone I know really well and it’s fun and goofy. Sometimes it’s super awkward because I don’t know someone and those are all enjoyable parts of the process. Early on, I thought I had to have a special deep connection to every single person. But that’s just not the reality of it. There’s an intimate moment and I do spend a lot of time thinking about the person, when I’m painting them, because I’m just looking at their image for hours and spending time with that. On my side, I think about them a lot.

JM: How do you work in your studio? It seems like you mostly just work on your portraits or do you work with a team? I’ve seen you do a mural before. What does your team look like?

LC: I did do a mural in Edmonton for Canadian Art and that was a really special thing because I got to hire youth to help me (who I had worked with at my previous job). That was nice. Kind of nerve-racking too because I normally do work completely solo. I’m very introverted in my studio. I like to be in control of all these aspects. I like to have my process a little more private. Making a mural was sort of the opposite of that because it’s on display. I don’t have a special mural process. I was very much creating a portrait on a large scale the way I would a normal painting. So it was kind of messy. I set up the composition. I had to change it. So I had to paint over the whole garage door (the surface for the mural) again because I didn’t put it in the exact place I wanted. So, it’s definitely on display. People are walking by. It was interesting to see the differences. I do prefer to work on my own and just have those introspective moments; that private time, I guess. But I think murals are a good way to challenge all those things that I feel like protect me and my process, and see what’s important and what isn’t.

JM: Why do you gravitate toward the people you represent?

LC: It ends up being who is around me. Some people I haven’t met in person but I’m inspired by. People in my own age group a lot of times. In the art world. I feel like I have a long list of people I’d love to paint. I wish I had all the time in the world to paint everybody. It ends up being who I am around physically and online. It ends up being like a lot of people that I am drawn to.

JM: Do you think that art plays a role in connecting us as urban Indigenous peoples?

LC: Going back to the way a lot of people read my work, they’ll say it’s about representation and identity. I think that makes sense that those are the first things that come to mind. But looking back, retroactively, I was trying to come up with an artist’s statement. I was just like, “I don’t know; I’m just trying something.” In the past, I would just be like, “Okay, what are people saying about it? Representation, identity, trauma, whatever.” But when I look back to all these portraits I made while I was in Edmonton, it was very much a way of me building my own community and meeting people. When I grew up, there was like no other Indigenous people for me to befriend or be around in rural Alberta. My own practice has been a way to find that connection. Thinking about Conor McNally’s film IIKAAKIIMAAT (2019), it feels like a similar thing. There’s some sort of exchange. He reached out to me to make this short film that touched on a part of my life. A few years later, I asked if I could paint him. It’s a really nice way to connect with each other and make things and spend time with each other in these different ways. That is a big part of Indigenous art and a lot of us connect with each other in those ways.

JM: Is there anything else you wanted to say about these themes that you feel like you didn’t get to say in this interview?

LC: I’m doing my MFA right now. I’m rethinking a lot of the things in my work. It’s hard to define my work because I don’t want it to become a defined thing in the same way as when we look at these anthropological portraits of Indigenous people. Like, [I’m presenting] a known thing. Like, this is how the [people I paint] look; this is how they relate to each other. [I’m rethinking] making us so definable and so measured. I’m thinking a lot about that in my work going forward: unknowability. I’m thinking about these images and how close I am to making anthropological works. How can I break out of that and think about something like freedom in my work and in these portraits? I don’t want to trap a person and be like, “This is who you are. This portrait defines you.” That’s what I’m doing in grad school: finding the words around my practice, which is hard. When I hear the word “representation,” I get freaked out a little. I don’t want people to feel like they have to always represent their community or something specific.