Thank you for joining me for this edition of I Saw Some Art. Let’s address a critical issue upfront: Palestine will be free. Social media platforms were recently inundated with images depicting demonstrations in major Canadian cities advocating for Palestine and demanding an immediate cessation of the siege, occupation, and ongoing atrocities in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. Indigenous communities from “the river to the sea” have united in a collective movement to denounce the unfolding genocide in Palestine, driven by imperialist rhetoric.

The narratives surrounding Indigenous peoples—from Palestine to Turtle Island—reflect the prevailing sentiments within settler-colonial societies. It is striking to witness the juxtaposition of watching Killers of the Flower Moon—nominated for several Academy Awards, yet having won none—while witnessing the ongoing genocide of Indigenous peoples in real-time.

Killers of the Flower Moon brought to mind my readings of Dante’s Inferno during my formative years as an undergrad. Dante Alighieri, an Italian poet and philosopher, is celebrated for being the first poet to incorporate common speech into his literary works. Before Dante, poetry was exclusively written in Latin, accessible only to the upper class and nobility. Dante’s works, however, resonated with the people of Italy and played a pivotal role in establishing a common language across Western Europe. Embedded within his writings is the early framework of social hierarchy, juxtaposed with patriarchy—wherein man, ordained by God, is placed above woman, child, and even community. By making literature accessible to the common “man,” Dante imbued men with a sense of godlike moral and logical reasoning, or so the Enlightenment dogmas say.

When I first encountered Dante’s Inferno, its depiction of the circles of hell struck me as a reflection of our earthly existence under settler-colonial regimes. Dante’s adherence to Christian symbolism instills the verses of Inferno, or Hell, with a profound resonance, resembling thinly veiled metaphors for the moral consequences of human embodiments on Earth.

For Dante, Hell is a landscape heavily influenced by Christian and colonizing dogmas, and serves as an allegory of the moral consequences of the flesh. To me, an NDN in 2024, Hell is the reign of Western colonialism and its doctrines, a dominance that not only demands scrutiny but also calls for its dismantling and the envisioning of alternatives. Hell is man, ordained with the power of God, serving as a tool for the conquest of those deemed lesser forms of life on Earth, where the circles of Hell are tightly bound. Hell is other people.

In contemporary discourse, if we examine the representation of Indigenous life, such as that depicted in Killers of the Flower Moon, it becomes evident that colonial narratives have persisted since the 14th Century. This enduring narrative suggests a troubling continuity, wherein Indigenous peoples are subjected to felt settlements akin to the infernal torments envisioned by Dante.

In Killers of the Flower Moon, the narrative centers around Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his Uncle William King Hale (Robert De Niro). The story unfolds as King and Ernest befriend the local Osage community, who possess intergenerational wealth across generations due to the discovery of oil within their territories. Ernest’s path intersects with Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), and under King’s guidance, he grows closer to her. Their relationship deepens, leading to marriage, and for a time, they find happiness together.

Meanwhile, a series of rapid murders targeting Mollie’s sisters and mother unfolds. The killings are marked by brutality, including a shooting and a public autopsy that gruesomely exposes Mollie’s sister’s shattered skull with doctors examining her brain. As the story progresses, it becomes clear to the audience that Ernest and King, affiliated with a secret white supremacist society, are orchestrating these murders of Osage individuals to secure Ernest’s inheritance, with Mollie ultimately becoming their target. Mollie’s health deteriorates significantly as Ernest poisons her insulin with a lethal combination of heroin, morphine, and a substance known as “atr,” leading to graphic scenes of her suffering from visions. The audience is confronted with rapid and horrific portrayals of the killings of Indigenous women and the depiction of suffering Mollie, reinforcing negative stereotypes about Indigenous women already prevalent in contemporary society.

Lily Gladstone’s performance has sparked profound reactions within Indigenous communities across North America. Following her Golden Globe win and Academy Award nomination for her portrayal, Indigenous peoples took to platforms like TikTok to celebrate a triumph for representation, instilling pride in their Indigenous identity. Indigenous TikTokers expressed a sentiment of feeling that Gladstone had been “robbed” of the Academy Award.

Similar waves of celebration and recognition swept through Indigenous communities on social media platforms like “Indigenous TikTok,” affectionately dubbed by its members, reminiscent of the response to the Vegas Stanley Knights winning the 2023 Stanley Cup. Before the victory, an announcer had struggled to pronounce the name of Dakota defenseman Zach Whitecloud, even resorting to mocking it during a live broadcast. However, when the Vegas Stanley Knights claimed the Stanley Cup, images of Whitecloud’s triumphant lap around the ice, hoisting the cup above his head, circulated widely on Indigenous TikTok. Accompanied by Kendrick Lamar lyrics—nah, a dollar might turn to a million and we all rich, that’s just how I feel—comments flooded in, affirming that his name would never be mispronounced again. Such moments of success hold a psychic significance, particularly considering the historical genocide of Indigenous peoples in North America.

All of this emphasizes that Lily Gladstone’s performance in Killers of the Flower Moon is NDN art at its pinnacle. In her portrayal of Mollie, I see echoes of every auntie who ever loved Gladstone, reflected in the quiet humility she imbued in the character and the discomfort she evoked in Ernest. Digital communication platforms like Indigenous TikTok have become a testament to the strong claiming and celebration of Gladstone and her performance.

Still, the casual passing of Indigenous death on film is nothing new. In a Twitter post Devry Jacobs of Reservation Dogs wrote, “Being Native, watching this movie was fucking hellfire. Imagine the worst atrocities committed against yr ancestors, then having to sit thru a movie explicitly filled w/ them, w/ the only respite being 30min long scenes of murderous white guys talking about/planning the killings.”

The portrayal of Indigenous women’s deaths in Killers of the Flower Moon is primarily framed within the context of the white men in their lives. While Scorsese’s intent seems to delve into a critical examination of whiteness, akin to a trend of films reinterpreting histories of “The West,” the execution falls short. Despite attempts at a deeper exploration, the cinematography still conveys a narrative steeped in Indigenous death and settler-colonial domination, while the central and well-developed storylines remain centered around white men. Even the underlying theme of critical whiteness feels superficial and disconnected from the broader discourse on critical whiteness in cinema, as explored by directors like Jordan Peele.

Ultimately, the film comes across as an identity crisis for a late-career director grappling with the implications of his predominantly white and masculinist body of work, and whether such bodies of work, and associated ideologies, will endure into the future. Given his substantial financial contributions to the loosely defined film department at NYU—now bearing his name—a trend emerges of memorializing and congratulating white administrators and creatives for their role in introducing “diverse” issues into aesthetic discussions. Ultimately, this psychic position relies on centering the white perspective—which critical theory has proven to be quite fragile—within discussions of Indigenous sovereignty.

The writing and visual language of Killers of the Flower Moon effectively depict a specific layer of colonial Hell on Earth: lust. Lust, the first circle of Incontinence in Dante’s Inferno, serves as the initial ring of Hell where punishment commences. It is a realm for those consumed by lust and those who have committed “carnal” offenses. According to Dante, carnal desire becomes a sin only when it overrides reason. Reason, we know, is only afforded to men in Hell on Earth. Poetically, Dante describes sinners here as souls tossed back and forth in an eternal storm. His portrayal acknowledges that carnal indulgence often involves two parties and thus cannot be solely attributed to individualism. However, Dante’s narrative also reconstructs a patriarchal archetype, as ancient as Adam and Eve, which suggests that men are not entirely culpable for acts of lust because women, with their allure and charms, also share responsibility for overtaking the reasoning of men. Figures like Cleopatra are depicted in Hell, ostensibly for sins related to beauty and their ability to incite desire in men, diverting them from reason.

Dante, of course, does not understand that desire, within a colonial Hell unfolding everywhere and all the time, is never equal. Recently a video spread across TikTok of an Indigenous woman who was zip-tied and being dragged into the basement of the Marlborough Hotel in Winnipeg. She commented on the original video stating that she had passed out and, when she woke up, she was being dragged into the basement of the hotel, which is when she started screaming. Indigenous communities in Winnipeg began gathering manifestations in the hotel as a call for justice and a reminder of the violent realities for the daughters of every colonial story ever shared between white peoples who lusted to dominate us psychically, sexually, and physically. This disturbing instance of the normalization of violence against Indigenous women in Canada follows over a year of activism within Indigenous communities in Winnipeg. This activism has been directed at the Winnipeg police, urging them to address systemic racism and conduct thorough searches of the landfill for the bodies of two missing Indigenous women: Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran.

Cinematography depicting the violent deaths and desecration of Indigenous women’s bodies goes beyond mere analogy—it carries terrifying implications for the safety of all those who embrace Indigenous femininity in contemporary societies. This portrayal reflects a disturbing lust for domination over Indigenous communities, masquerading as support for our narratives. In truth, it aligns with the very forces that have historically sought to exploit and harm us. Hell, in this context, truly seems populated by those who have sought to violate our bodies and spirits.

The notion that any Indigenous representation is good representation no longer holds true. While I acknowledge the progress made by Indigenous leaders in film who have paved the way for representation, we are also witnessing an “identity” crisis in film. There is currently an unprecedented influx of “Indigenous” actors, producers, directors, and cinematographers who are not affiliated with recognized Indigenous communities, a phenomenon stemming from efforts to push for representation in film. It is imperative that we scrutinize the stories we label as “Indigenous,” and ensure that these narratives are led by Indigenous peoples. This is not only crucial for preserving and protecting our cultures but also for safeguarding our peoples.

The circulation of Killers of the Flower Moon through the cultural consciousness of North American peoples exemplifies what is commonly known as the John Smith Syndrome. American and Canadian audiences often struggle to engage with media about Indigenous peoples unless they are also portrayed. This reluctance stems from a desire among white viewers to avoid confronting feelings of guilt when consuming such media. Instead, they seek narratives that position them as positive agents within a structure from which they benefit. White audiences gravitate toward stories where they can envision themselves as heroes, such as Jesse Plemons’ character, saving the supposedly powerless and vulnerable Indigenous communities. However, considering the historical genocide of Indigenous peoples that has transpired in North America, it’s evident that white people likely would not have acted any differently than their ancestors who participated in the clearing of the plains.

Discussions of settler-colonialism in contemporary contexts often overlook the ongoing reality that colonialism persists within Canada. Indigenous peoples are consistently displaced from their territories within Canadian borders for settler-colonial development projects. tīná gúyáńí is an artist collective comprising a parent and child duo—seth cardinal dodginghorse and Glenna Cardinal. In their individual art practice, seth cardinal dodginghorse explores the histories of their family forcibly removed from their homes and land for the construction of the South West Calgary Ring Road. tīná gúyáńí’s 2023 exhibition “her name,” showcased at Gallery TPW in Toronto, employs affective cinematography and sound to unveil the embodied Indigenous experience of settler-colonialism, delving beneath the surface to reveal the deep-rooted impacts that transcend easily visible physical manifestations.

“her name,” above all, is a story. This story is thread throughout the film installation created for the exhibition, with Glenna Cardinal’s personal journey serving as the driving force behind the film’s dialogue. The story begins with Glenna Cardinal—when she began her studies at nuhelot’ine thaiyots’i nistameyimâkanak (Blue Quills University)—but also begins before her, with Glenna’s paternal nehiyaw family members attending Blue Quills Residential School. It encompasses the story of the artists’ family and echoes the experiences of countless Native families across Canada impacted by the legacy of Residential Schools. Yet, rather than advocating for a monolithic pursuit of “reconciliation” that relies on pleading for aid from the abuser or appealing to the oppressor for inclusion, the narrative focuses on community-building. It is the story of one family, one lineage, one Native community—a single reality amidst a myriad of experiences.

As I stepped into the exhibition space for “her name,” I was met with Native “grandpa couches“—with wood frames, worn plaid upholstery, and blue pendleton blankets—and matching chairs, creating the illusion of a cozy and inviting atmosphere. Without hesitation, I settled into one of the couches, feeling as though I had been welcomed into the space by a familiar. However, there was a subtle irony in the juxtaposition of the comfortable seating and the film projected on the wall across from the couches. What stood out most to me was the haunting soundtrack accompanying the film and its dialogue. The deep, groaning noise—ending with moaning and flanging guitar riffs—created an atmosphere that was both immersive and overwhelming, leaving me with a sense of unease. The film’s music was scored, performed, and written by seth cardinal dodginghorse. The noise conveys raw emotion, coursing through your body with an impending intensity.

Towards the end of my visit to the installation, a parent entered the gallery with their young child. They spent some time in the exhibition before the child began to cry. The intentionally unsettling noise succeeded in its aim, provoking a reaction from the child. This interaction piqued my interest. In broader Canadian society, the discourse surrounding reconciliation has, in a sense, sanitized the realities of Residential Schools and the profound trauma they inflicted. Institutional reconciliation suggests to settlers that they can educate their way to forgiveness. However, Native communities cannot simply educate themselves out of the intergenerational trauma stemming from Residential Schools.

The experience of the children who attended Residential Schools encompasses abuse, harm, loneliness, and death. It is intriguing to witness a white parent come to this installation, anticipating an educational platform that would embrace them with generosity, only to depart with the same anguish our ancestors endured within the walls of Residential Schools, etched into their very beings, if they were fortunate enough to leave at all.

Could the noise in the installation be interpreted as the uneasiness felt by the artists when the bodies of Native children were found at Blue Quills? Blue Quills was once the site of the Blue Quills Indian Residential School. The use of ground-penetrating radar to search for “anomalies” (a sanitized term for the “possibility” of the buried bodies of Native children) is a haunting reminder of the murders committed by Canada and the Catholic Church. Glenna Cardinal’s often hushed reality was knowledge that her aunt attended the Blue Quills Indian Residential School and died there, and realizing her aunt’s grave is unknown. This sets her family on a journey to find the name of their aunt. The presence of researchers wearing orange shirts, a color used to commemorate the horrific history of Residential Schools in Canada, further underscores the significance of this exploration.

How peculiar it is to inhabit one’s own territories yet feel utterly alienated and gripped with fear—a sensation akin to a prairie gothic. You could be seated on your favorite couch, yet consumed with an internal terror. The prairie gothic theme, encapsulating domestic horror manifested through everyday relations, reverberates throughout the film “her name” due to the deliberate decision to film and treat with an old, nostalgic aesthetic—reminiscent of a collage of aged photos discovered in the attic of an old house. Other scenes take place in the school, absent of all the people, children, who once attended. There is an eerie quiet to this exclusion of Indigenous bodies in the space, against the visuals of sterile hallways and empty rooms. One shot shows a view out the window from inside the school. Was this the view the artists’ ancestors who attended the school saw, when they prayed for their return home?

This paradoxically disembodied yet embodied experience evokes Dante’s seventh circle of hell: violence. In Dante’s Inferno, violence is perverted for settler-colonial ends. Those who have committed violence against their neighbors find themselves condemned here, yet the harm inflicted upon neighbors is reduced to crimes against property and private ownership. This warped fate reflects the plight of Indigenous peoples living under settler-colonial rule—a Hell on Earth, where they endure perpetual violent displacement from their territories, only to be gaslit by their oppressors, labeled as violent for any attempt to assert their freedom. Violence, in this inferno, manifests as the safeguarding of private property and imperialist wealth through surveillance—a selective view of neighbor that excludes those who have been dispossessed of their territory and place. Indigenous peoples, trapped in this surveillance state, seem destined to eternally suffer in Phlegethon, a river of blood and fire—perhaps a good name for the audio track for “her name.”

While Indigenous peoples globally endure Hell-like atrocities under settler-colonial rule, their suffering is not a tragedy for mere consumption, as the haunting audio track of “her name” suggests. The widespread application of “healing” has faced scrutiny within the intersection of affect studies and Indigenous studies. How can the Indigenous body embark on a healing journey while enduring a Hell on Earth? Yet, Glenna Cardinal’s voice serves as a steadfast beacon for her child, guiding seth cardinal dodginghorse away from bitterness and resentment and toward embracing personal responsibility for their own healing—lest we repeat. This resonance of intergenerational healing underscores the importance of addressing the embodied realities of the Residential School legacy within Native families, rather than monetizing those realities for political discourse through institutional and abstracted lenses.

One pathway to healing represented in “her name” is healing through kinship to kin and land. Some of the most striking images in the film for “her name” are the signs leading into the artists’ territory, Saddle Lake Cree Nation: “Saddle Lake Cree Nation welcomes you;” “Please keep Saddle Lake clean;” and “Treaty 6 territory.” The enduring presence of signs contest the nostalgic mood of the film, another ironic state for the viewer. The land—water—are central to this breaking down of time and space through Indigenous knowledge within the installation. In some segments of the film, images of the water are cut together, like a collage of slides or negatives, until they blur unintelligibility into one body of water. Maybe this isn’t the past, but an intimate view inside the home films of one family impacted by disconnection to their territories, and the role Residential School played in the disconnection.

Healing through community, kinship, and connection to the land is further emphasized when, on the day of the radar search, the artists’ father and grandfather surprises them. He takes them walking across the grasslands, and their shadows dance upon their territories. Images of the vast grasslands and expansive sky envelop the scene. He shows them his old house, now in ruins on the land, surrounded by various signs of decay. These are some of the most tender images in the film, somehow layering horror with profound love—the NDN way.

Still, their family remains here. Not victims—nay, warriors. One visual that returns many times throughout the film is the artists touching the side of buildings—like Blue Quills—with a stick. Counting coup—touching your enemy with a stick rather than killing them, just to let them know that you could have killed them, but didn’t—is a wartime practice in Tsuut’ina and Blackfoot culture. This visual is a response to the forcible presence of settler-colonialism in Canada. The Canadian state has removed this family from their lands, and enacted harm on this family. Yet, under Tsuut’ina and Blackfoot sacred laws, the honorable thing to do is to let your enemy survive, and not seek vengeance.

“her name” demonstrates that discussions of Residential Schools need not always delve into the gruesome details. Sometimes, creating a space for mutual healing, for coming together, holds far greater significance than attempting to appease our oppressors by recounting graphic atrocities. The colonial discourse of justice often demands that we continuously diminish ourselves to the position of the colonized, the perpetual victim, in order to seek acknowledgment of our humanity within its confines. “her name” showcases one Native family actively resisting this pressure, refusing to cater to the colonial gaze of institutions that claim to seek reconciliation.

In the seventh circle of Hell, amidst those who have committed acts of violence or, in a colonial Hello on Earth, endure gaslighting for the violence perpetrated against them, dwell individuals guilty of crimes against God, Art, and nature. Drawing upon the imagery of the Abrahamic narrative of Sodom and Gomorrah—cities purportedly obliterated due to their perceived depravity—those who populate this infernal realm suffer the relentless onslaught of fire descending gradually from the heavens. Among the condemned are numerous souls, including witches and other women deemed uncontrollable (the Blasphemers), as well as the queer (sodomites).

Dante further posits the presence of Userers, those who have committed violence against Art. According to Dante’s reasoning, Art is the progeny of God, intended solely to uphold the colonial doctrines of Man’s imperialist Hell on Earth. Only two sanctioned modes of creative labor exist within colonial Hell: the extraction of wealth from natural resources, and the exploitation of human labor and activity to accrue wealth. Implicit in both is the pursuit of capital within a colonial and imperialist framework of commerce and ownership. It is within such a perverse system that man deludes himself into believing in his entitlement to possess both land and life, viewing it as his duty and prerogative. In this contemporary manifestation of Hell on Earth, who dares to oppose the relentless accumulation of wealth through the plundering of land and the subjugation of human bodies, manifested in the possession and brutal exploitation of Black and brown bodies?

Artworks by Cree and Métis artist Michelle Sound, hailing from Wapsewsipi Swan River First Nation, featured in the 2023 Burnaby Art Gallery exhibition “Kindred Tracings,” poignantly address the ongoing alienation experienced by Indigenous peoples removed from their land. They also underscore the stark reality of the loss of Indigenous lives when they resist land appropriation—a fundamental aspect of colonialism, perpetually fueled by greed.

Sound’s contributions to “Kindred Tracings” serve as a visual exploration of the language and concepts that marked her ancestral territory. “Kindred Tracings” showcases a curated selection of works from Sound’s personal collection, each piece depicting the abstraction of territory and bodies—representing peoples, families, and children—serving the agendas that so effortlessly and callously roll off the tongues of imperialists. It’s remarkable how languages that actively genocided Indigenous peoples from their lands have been repurposed as tools to justify the ongoing displacement of Indigenous descendants.

Cartographies played a pivotal role in facilitating the colonial appropriation of land, and the naturalization of violence committed against Indigenous bodies in service of colonial ownership over land. Often crafted using the knowledge provided by Indigenous peoples to explorers, the earliest maps depicting the territories that would eventually become subsumed under the project of Canada were drafted by the would-be colonizers who did the extracting. Rivers, lakes, and villages were meticulously charted based on the goodwill and trust extended by Indigenous communities, who believed they were forging kinship rather than giving permission to be forever caught in a violent embrace.

These cartographies serve as tangible representations of the linguistic exchanges that, when abstracted, functioned to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their lands and perpetually exploit Indigenous relations to those territories. Each line and boundary on these maps symbolizes the systematic erasure of Indigenous presence and the relentless exploitation of their ancestral lands.

Presented as large-scale prints within the exhibition, Sound’s work challenges viewers to confront the historical complexities embedded within colonial cartography. This tension is explored in Sound’s artwork Sipikiskisiw (Remembers Far Back) (2022). The work consists of images of an archival photo and map on paper, embroidery thread, rick rack, vintage beads, bugle beads, glass seed beads, caribou tufting, and porcupine quills. The map and photo are rendered in a collage-like form: the photo is a 19th century image of Indigenous men and tipis at Fort Edmonton, and the map is a survey map of Papaschase Reserve from 1899. Sound’s family–her great, great kokum–was from Papaschase and Treaty 6.

The knowledge appropriated from Indigenous peoples by settlers in an attempt to dominate the land that became Canada is now exploited through the surveying of land. Surveying, or rather, surveillance of Indigenous communities, is still the first step to removing Indigenous peoples from the lands they relate to, so would-be colonizers may plunder the land. Much like Glenna Cardinal and seth cardinal dodginghorse’s community—and their removal from their territories, long after the Treaties were signed—the Treaty peoples of Papachase had their Treaties denied and their lands encroached upon, when they were removed from their land for the expansion of the project of Canadian settler-colonialism in the prairies.

Sound is renowned for her bold utilization of color, and “Kindred Tracings” showcases Sound’s masterful use of color, with vivid greens, oranges, and other hues obscuring the documents that once served as instruments for extracting Indigenous land and life. It’s Sound’s most confidently executed use of color yet, and blends the composition into a symbol of healing, akin to the reversal of a sickness, spreading across the land and through our languages.

In Sipikiskisiw (Remembers Far Back) (2022), a photograph of tipis breaks the landscape and, on the other side of the composition, a land distribution map is revealed. Brightly colored thread and tufting, multicolor beadwork and quillwork, and orange stitching—the vitality of Indigenous life and love—weave all these disparate pieces together. Colors that transcend colonial meaning, time, and space, and hold all these broken promises together throughout the changing faces of Canada. There is no repair here, except Indigenous futures. How can we look again and again to spaces that have denied our Treaties. How can you beg an imperialist murderous force for mercy, with no reprieve, and yet they still expect hope for repair?

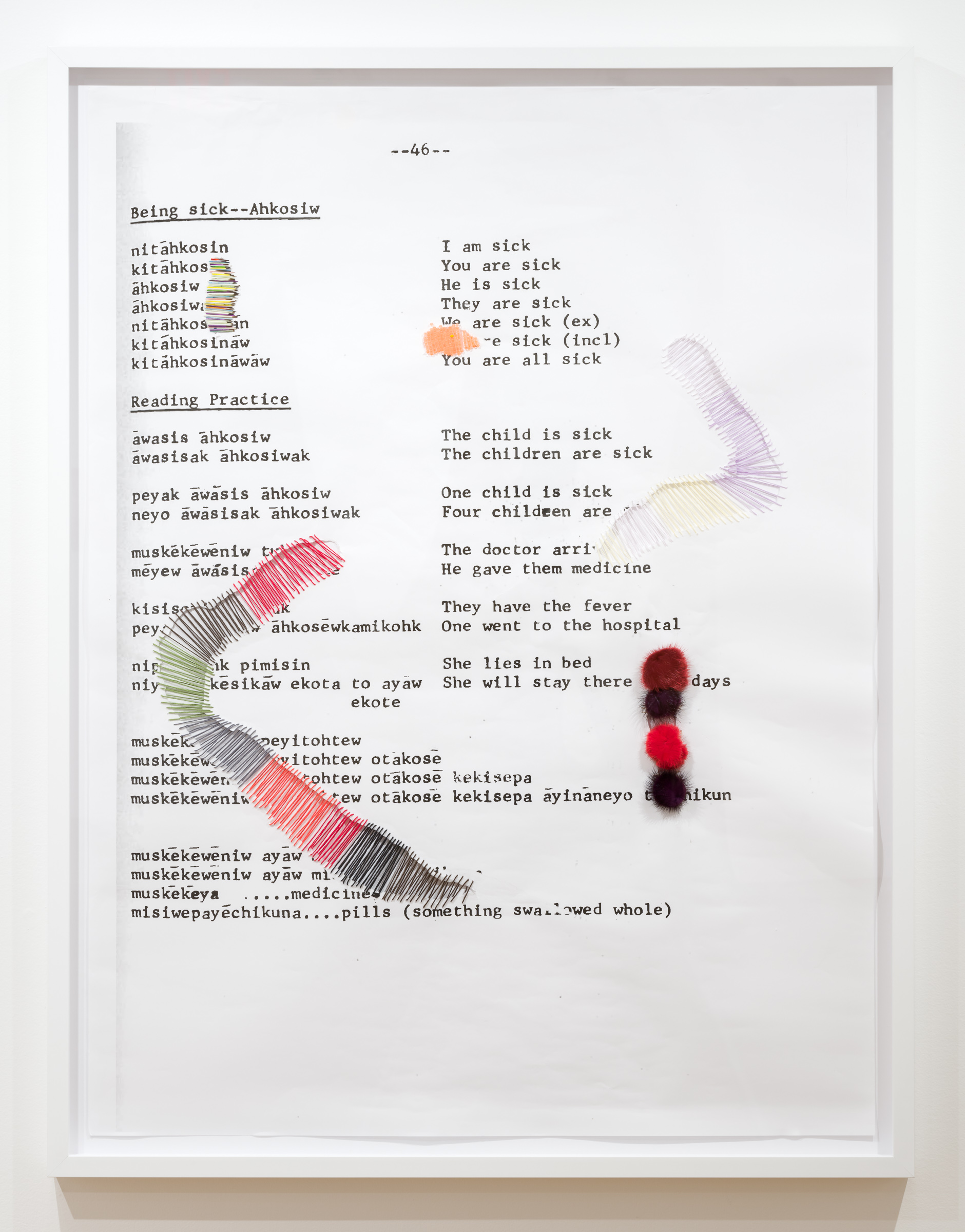

In Sickness / Being Sick (2023), Sound again employs the technique of presenting archival prints on paper, interrupted by embroidery thread, yarn, seed beads, dyed mink fur, and porcupine quills in bright shades of orange, green, and yellow. The composition consists of pages from language dictionaries dealing with words related to illness. Through a didactic in the gallery, the viewer learns that these are worksheets from a Nehiyawewin language book the artist’s mother has had since the 1970s. The phrase “being sick” is marked with the color orange, evoking the color usually associated with reconciliation, and healing from histories and contemporary affect related to the Residential School system in Canada. “Healing practice” is marked with red and black stitching and tufting—two of the colors from the medicine wheel.

Nehiyawewin, or the Plains Cree language, is not static. It evolved over time to include new terms that the settlers introduced in their projects of settlement. I wonder what are the words that the descendants of Palestinians today will look back at as newly introduced to describe the atrocities that they have been forced to witness?

Conveying to the delicate sensibilities of the imperialist ego that land shapes language and peoples—not the other way around—poses a challenge. The land has never, and will never, consent to the imperialist exploitation that constitutes the ultimate affront to the Indigenous Peoples that the land relates to. Within a colonial Hell on Earth, this exploitation represents the gravest crime against nature and all forms of Art that emanate from it.

The deliberate choice of white frames for Sound’s compositions serve to blur the boundaries between the pieces and the surrounding gallery space. This deliberate blurring gestures towards the fragile scaffolding of not only the gallery itself, but also the fragile egos that sustain the settler-colonial mythologies of nations such as Canada to Israel—nations built upon narratives of victimhood that align with imperialist agendas, spanning from Treaty 8 and Treaty 6 to Palestine.