sâkihito-maskihkiy acâhkosiwikamikohk

May 20, 2016

by Jas M. Morgan

Indigenous Artists and the Dystopian Now

Armed with spirit and the teachings of our ancestors, all our relations behind us, we are living the Indigenous future. We are the descendants of a future imaginary that has already passed; the outcome of the intentions, resistance, and survivance of our ancestors. Simultaneously in the future and the past, we are living in the “dystopian now,” as Molly Swain of the podcast Métis in Space has named it. Indigenous peoples are using our own technological traditions—our worldviews, our languages, our stories, and our kinship—as guiding principles in imagining possible futures for ourselves and our communities. As Erica Lee has described, “In knowing the histories of our relations and of this land, we find the knowledge to recreate all that our worlds would’ve been if not for the interruption of colonization.”

Indigenous artists on Turtle Island (the anishinaabe description of the lands we now call Canada, as recorded on birch bark scrolls) have engaged with tropes of science fiction in their artwork: alien figures straight out of Space Invaders, post-apocalyptic landscapes that bare eerie resemblance to contemporary landscapes devastated by resource extraction, and unidentified flying objects that mark first contact with otherworldly beings. Speculative visualities are used to project Indigenous life into the future imaginary, subverting the death imaginary ascribed to Indigenous bodies within settler colonial discourse. As Andrea Smith has written, the death imaginary purports that Indigenous peoples must always be disappearing in order to legitimize settler occupation and the Canadian state. Settler art, in its imagining of Indigenous disappearance, its representation of the romanticized but dying homogenized Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, offers a location for Indigenous artists to contest colonial representations in art with their own futuristic imaginings and art practices—art practices that weave together tradition and technology, fusing them together into a future present.

The future imaginary and its catalogue of science fictive imageries affords Indigenous artists a creative space to respond to the dystopian now, grounding their cultural resurgence in contextual and relational practices. Indigenous artists have no problem portraying possible undesirable futures wherein colonial capitalist greed has resulted in the subjugation of life within all creation, because these narratives are evocative of our known realities. We have realized the apocalypse now, and we are living in a dystopian settler-occupied oligarchy fuelled by resource extraction and environmental contamination, completely alternative to our traditional ways of being and knowing.

Despite dystopic realities, the possibilities of love and kinship as resurgence in the face of ecological disaster are a visceral narrative for Indigenous peoples. Indigenous women and two-spirit peoples have consistently employed kinship and love within their communities in order to positively transform contemporary colonial realities for their kin.

Lou Catherine Cornum has considered the advanced technologies of kinship that Indigenous peoples possess for intergalactic engagement, offering us the concept of kinship as technology: “The Indian in space seeks to feel at home, to understand her perceived strangeness by asking: why can’t indigenous peoples also project ourselves among the stars? Might our collective visions of the cosmos forge better relationships here on earth and in the present than colonial visions of the final frontier?” Cultural knowledge of nehiyaw-anishinaabe kinship grounds my analysis of Indigenous artists who, in the face of misrepresentation and erasure within settler art, imagine and create themselves into being using speculative visualities— a body of work I have found particularly evocative and transformative to my own imaginings of the Indigenous future.

Indigenous Technologies

In their depictions of the future imaginary, contemporary Indigenous artists on Turtle Island have tended toward a contextual ideology of resurgence, one based in love and kinship, imagining a better, prosperous, and kinder future for all life within the galaxies. In her work Islands of Decolonial Love Leanne Simpson traces a decolonial ethic of love, each “island” a song or story addressing the complexity of interactions between animate beings in the contact zone. Political and philosophical thinkers have scoffed at love as something outside of formal thought or action. Marxists, perhaps, would argue against corrupt forms of love they perceive as sentimental bourgeoisie platitudes, like those described by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, seeing love as a biopolitical moment born from our capitalistic tendencies and situated within actions of obligation. Sovereigntist, decolonial, and/or masculinist scholars too might denounce love, mistakenly associating its ethic with neoliberal state-led and/or settler-led attempts to reconcile relations with Indigenous peoples. I’m interested in what is lost in such analyses, namely: a central focus on Indigenous ways of being and knowing, like kinship, as well as Indigenous women’s and two-spirit peoples’ essential roles in guiding our communities toward a truly emancipatory future.

I want to be careful here when teetering on the language of reconciliation, as I know it’s a contentious one. I am not describing a politic of recognition led by settlers or by the state, but rather, an ethical concept I experience within all facets of Indigenous life: being through kinship. I am perplexed by decolonial thought that hierarchically dichotomizes land work and relational work, favouring decolonization scholarship over reconciliatory action. Such rhetoric tends towards infantilizing those Indigenous peoples who exercise agency in their interactions with the state, including elders. While decolonial scholars consistently give lip service to centring Indigenous thought, they ultimately still envision Indigenous futurities as linked to scholarly permissible conceptions of decolonization. What does this mean when Indigenous peoples from within my own community don’t identify with the exclusionary academic discourse of decolonization, and centre the language of reconciliation in their own attempts to heal community?

Like my kin before me, I would argue that a project of Indigenous resurgence is nothing, is inanimate, without an ethics of love and kinship as a guiding principle. True deliverance from settler colonial occupation finds its foundation in Indigenous knowledges that understand land, love, and life as one and the same. In her book Thunder in My Soul Patricia Monture-Angus describes the concept of “justice as healing,” which includes both recentering women within all political aspects of Indigenous community and establishing meaningful external relations with settler communities in harm reductive ways. I’m also reminded of Leanne Simpson’s evocation of Monture-Angus in Dancing on our Turtle’s Back, reinforcing that “self-determination and sovereignty begin at home.”

It doesn’t surprise me that Indigenous women and two-spirit people like Erica Lee, Christi Belcourt, Chelsea Vowel, and Maria Campbell are leading conversations around reconciliation, because the language of reconciliation bears resemblance to the language of kinship and, therefore, the relational work they already do within community—an often invisibilized labour. Work based in restoring relationships between one another that have been eroded by colonialism. Work that understands theory as conceptual and grounds itself in reducing the harmful effects of colonial violence on our bodies, minds, and spirits.

While Eve Tuck necessarily reminded us that decolonization is not a metaphor, the Indigenous peoples in my community also recognize the dire need to support one another’s survivance, right here, right now. As someone who has consistently received teachings from nôhkomak (grandmothers) and nisikosak (aunties) around relationality and kinship, I can see how the language of reconciliation parallels an ethic of kinship. While I may prefer to call a political act of love decolonial love or even a return to kinship, I also want to honour the truth of my kin who choose to describe such work as reconciliation. In midst of the dystopian now—an apocalypse come to life for Indigenous peoples—we cannot wait for some faraway time when the land has been returned to heal the embodied effects of colonialism that are literally killing us everyday. We must liberate both land and life by actively honouring our responsibilities to kinship in this moment, fostering good relations within all creation in our intentions and actions. Contemporary Indigenous artists on Turtle Island speak these ideologies of kinship in their work, using its advanced technologies in conjunction with speculative visual cultures to project their communities into the future imaginary.

Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurism

Access to art historical methodologies and museum studies within academic art history departments has exposed me to the cultural life of my relations both north and south of the medicine line, including some work as old as 100 AD. However, as a nehiyaw-anishinaabe person, I also recognize the complexity of my relationship to archival and museum practices on Turtle Island. I’m hesitant to call non-consensually and invasively unearthed cultural objects “artifacts” or “art,” descriptors allocated to them by settler appropriators and grave robbers. To see the cultural objects of my ancestors displayed behind glass cases in sterile museums, void of the life and meaning they held within community, feels like another facet of the death imaginary ascribed to Indigenous communities within the arts. Nevertheless, access to the cultural objects of my ancestors has been visceral and has afforded me representations of Indigenous knowledges, experiences, stories, and life unadulterated by the gaze of the settler academy. As Sara Ahmed would say, representations free of translation by the “stranger.”

Inuit art offers a particularly interesting location for the future imaginary because of the proximity to first contact moments with settler society. For some Inuit, close encounters with an alien culture, outside of anything within the worlds they have ever known, have happened within their lifetime. Inuit artists have depicted their early interactions with settlers in speculative ways using futuristic imaginative concepts: a future imagery in the present. One jarring example is Ovilu Tunnillie’s green stone carving This Has Touched My Life (1991-92), a representation of the artist’s experience of being removed from her home and taken to an infirmary in the South, her first time away from her home in the North. The nurses who are escorting Tunnillie are wearing veiled hats but, in Tunnillie’s depiction, the hats look like space helmets.

Pudlo Pudlat is often revered for being the first Inuk to feature Western technology in his work; his lithograph Aeroplane (1976) even appeared on a Canadian postage stamp.The irony, of course, is that the Baffin Island Inuk artist’s usage of speculative visualities actually critically engages with destructive colonial technologies rather than condoning them. In Pudlat’s lithograph Imposed Migration (1986), he depicts an otherworldly flying object: a UFO, if you will. The UFO is cabled to a variety of northern animals: a walrus, a bear, and a buffalo, and is lifting them off the ground, transplanting them to new territories. The absurdity is transparent. To remove kin from their home territories is to separate them from their context, to remove their very essence and connection to the land. Here Pudlat is openly denouncing the colonial project of forced removal and migration inflicted on Inuit communities in the North.

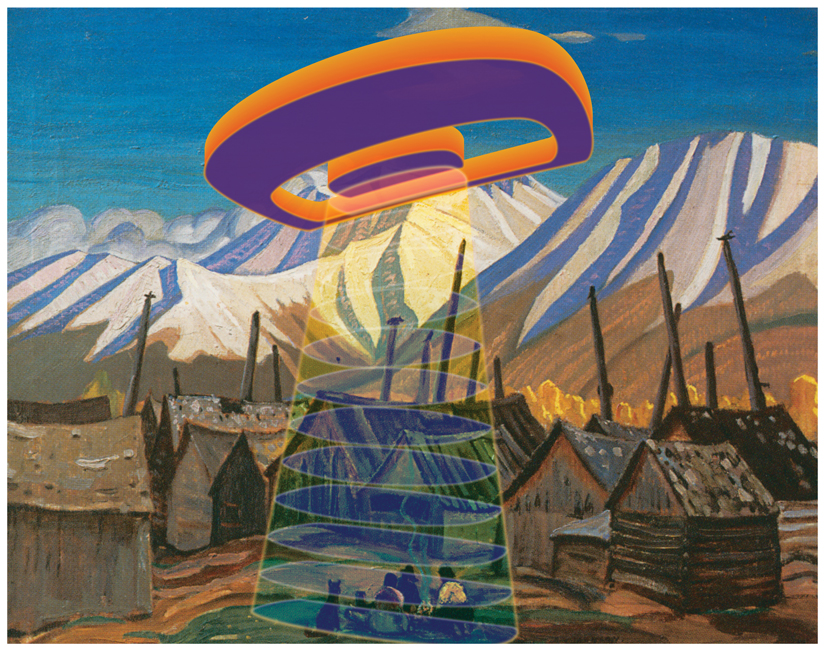

Ligwilda’xw Kwakwaka’wakw artist Sonny Assu has also engaged with diasporic Indigenous identities using tropes of futurity. In his series Interventions on the Imaginary, Assu adds digitally created alien-like figures to settler depictions of Indigenous peoples at early contact. In doing so, Assu re-appropriates the visuals of the settler art he has selected, contesting the romanticized and orientalized representation of Indigenous peoples as what some have called “the imaginary Indian” of the colonial art period. They‘re Coming! Quick! I have a better hiding place for you. Dorvan V, you’ll love it depicts an alien force entering a pre-colonial Indigenous community, as if to remove or exile the Indigenous population, beaming them up into an otherworldly “space invader” object. Assu depicts Indigenous peoples in migration, within a so-called “fourth world,” living in diasporas within their own territories. These figures have been forced off of their home territories, their bodies propelled through occupied space by an alien force, whose gaze they attempt to hide from.

Assu, Pudlat, and Tunnillie all deal with themes of displacement within the artworks previously discussed, relating these experiences to dislocation from kin and kinship. At the centre of these removals from community and disruptions of Indigenous ways of life is a distrust of the ominous alien force that seeks to either abduct or annihilate them. Rather than the otherworldly aliens from space depicted in the artwork, the artists are exposing their experiences of the settler-colonial project that seeks to displace and remove them from the land. This dislocation from their communities, from kinship ways, is a fracture to their very identities as Indigenous peoples. Dystopian science fictive futures are reconciled by kinship, and Indigenous futures are depicted in resurgent arts practices through self-determined representations. Art is both the means to project Indigenous life into the stars and the space canoe we use to paddle through these imagined galaxies. Art becomes a medicinal practice, healing our spirits, minds, and bodies as we move into possible futures.

Erin Marie Konsmo explores expressions of kinship and the dystopian now in several of her works. While I’m crediting Konsmo for her work, Konsmo herself has been hesitant to describe her work using individualistic pronouns, viewing her art as coming from community rather than solely from herself. Art is a part of all Indigenous life and art practice should, too, be based in principles of kinship. I recently had the opportunity to attend the vernissage for Dayna Danger’s and Cecilia Kavara Verran’s exhibit Disrupt Archive, curated by Heather Igloliorte at La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse in Montreal. During the artist talk, Igloliorte noted that it is often claimed Indigenous languages don’t have a singular word for art. The nehiyaw language, for instance, does not have a word that translates exactly into English as “art” or “artist.” However, in the exhibit Igloliorte reminds the audience that “art” is actually a part of everything we do in community, a part of all language.

Konsmo’s artwork Discovery is Toxic: Indigenous Women on the Frontline of Environmental and Reproductive Justice depicts an Indigenous figure scaled to fit into the landscape, as if the figure were itself a part of the land. A gas mask hangs from around the figure’s neck. Indigenous bodies are interrupted by settler colonial occupation, ships that bring with them a toxic commerce and colonizing religion—what the Native Youth Sexual Health Network has called environmental violence. Settler occupation is unnatural and has resulted in the subjugation of all Indigenous life, including land. The result is a post-apocalyptic environmental wasteland made of our territories and the embodied complexities of ecological warfare, including within the reproductive life of our communities. As the title suggests, it is kinship that frees the land and our bodies from the dystopian now. Indigenous women and two-spirit people are re-situating themselves as leaders of community, resisting settler colonial occupation and environmental violence, and resurging on the land through kinship and love.

Contemporary Indigenous artists on Turtle Island convey kinship in their artworks to envisage resurgence outside of cissexist and heteronormative relations. Accounting for the intricate and multiple ways we interact as interconnected communities puts us in a position to consider the location, or lack thereof, of two-spirit people within conceptions of Indigenous resurgence and peoplehood. It was Billy-Ray Belcourt who questioned which of our peoples are actually represented in the Indigenous future, borrowing from Gayatri Spivak to ask: “Can the other of Native Studies speak?”

Louis Esmé has also considered the future of our genders, sexualities, and ways of loving within interpretations of Indigenous futurities. Esmé asks: What space exists for our gender variant and sexually diverse Indigenous communities in the future imaginary? In their work we have come back for our bodies Esmé portrays two figures projected into the stars, fluid not only in gender, but in spirit and body as well. Esmé reminds us that Indigenous futures must include a return to our traditional ways of understanding gender: outside of the colonial gender binary, returning balance between the genders through kinship. Esmé proposes a restoration of two-spirit life within Indigenous community, actively remembering our traditions of gender fluidity and sexual diversity, in order to create a future imaginary that is responsive and respectful to the multiplicity of ways Indigenous peoples express their self-determined genders and sexualities.

Dayna Danger’s work for Disrupt Archive asks that Indigenous communities consider how our own sexualities and genders factor into our future imaginaries—what Qwo-Li Driskill has called a sovereign erotic. Danger presents a series of photographs featuring Indigenous models wearing black leather BDSM fetish masks adorned with rows upon rows of black matte and glossy beads. One mask prominently featured a labrys, a symbol associated with lesbian feminism or radical feminism. Danger produced the masks with the help of Indigenous relations from among her community. Hours of painstaking care and love were put into the masks, just as would be put into any beading project. The image of beading entire masks of leather evokes the literal blood, sweat, and tears integrated into the work itself.

Indigenous peoples’ sexualities are frequently equated to histories of sexual violence, commodified and institutionalized by settlers seeking to dominate, discipline, and control Indigenous bodies. Danger’s use of the leather BDSM mask references the kink community as a space to explore complicated dynamics of sexuality, gender, and power in a consensual and feminist manner. Danger engages with her own medicine, beading, in order to mark kink as a space for healing colonial trauma. There is no shame in this action. Here the models’ gender expressions and sensual lives are integral to their resurgent identities as Indigenous peoples.

Every day, Indigenous peoples are restoring their beings, bodies, genders, sexualities, and reproductive lives from colonial institutions through play, self-representation, and sexual self-determination. Enacting kinship in their art, the Indigenous artists discussed here embody the past and future in their present representations, projecting decolonial love and kinship ways into the cosmos. The future imaginary becomes a realm within which Indigenous artists express disconnection from kinship and land, a medicinal space to imagine new futures for Indigenous life—ways of being, relating, resisting, and resurging through love.

—

ABOUT

Jas M. Morgan is an anishinaabe-nehiyaw writer, curator, community organizer, and researcher currently residing in Tio’tia:ke/Mooniyang (Montreal). They are the co-founder of the Indigenous Women and Two-Spirit Harm Reduction Coalition as well as the Indigenous Arts Council, and a MA candidate in the Art History department at Concordia University. Tweets at @notvanishing; blogs at aabitagiizhig.

Cover image: Hoop in the Cloud by Wendy Redstar

“Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurisms” is from our FUTURES issue (spring 2016)