May 18, 2016

by Pree Rehal

Fandoms and conventions are uncomfortable spaces for brown and black women. I’m not a passive fan: I don’t merely like or enjoy the media I consume, I love it. This love takes shape in the form of cosplay, the fan activity of dressing up as a character from popular culture: film, shows, books… but honestly, you could cosplay a character that hasn’t been “published” in any way. I spend hours researching and planning particular kinds of cosplay representations—from characters that already exist to some that I invent—but this is standard practice in costume play. While I used to cosplay mostly to explore gender, I’ve become interested in using cosplay to challenge the future and the whiteness of the media I enjoy.

While the majority of cosplayers at conventions (cons) are non-binary people and women, both cis and trans, very few of them are racialized. By very few, I mean I’ve never met or seen another woman or femme of colour at a con. Unconventional cosplay, or cosplay that manipulates canon, is becoming increasingly popular in North America. This usually looks like women and femme cosplayers playing characters who are, within their given source material, cis men. When I first started cosplaying, my cosplaying was consistent with this trend: I began by playing with gender.

The prevalence of cosplays that cross gender lines like this is, I think, attributable to two things. First, there is a widespread lack of characters who aren’t cis men in popular art. Second, characters who aren’t cis men are often not multidimensional in any way. For example, when I first started cosplaying, I was drawn to characters coded as male in their source material because as a non-thin woman, I felt limited by the costumes women characters so often wear: they’re no more comfortable or forgiving than swimwear. And the issue wasn’t just that the articles of clothing were small, but that my body is different than two-dimensional comic book characters, and I am curvier than most white women on television. Beyond costuming, another imperative performative component of cosplay is posing. Posing in ways the cosplay community (or popular arts culture as a whole) deems feminine simply didn’t appeal to me. I don’t want to be subject to the convention’s male gaze when I design, pose, and “play” in my cosplays.

The cosplaying in effect when women play characters who are men in their source material can happen in different ways: binary-swapping and crossplaying are two common ones. I often used to binary-swap: I would change the gender of a character in my cosplay. The cosplay community refers to binary-swapping more commonly as “Rule 63,” “gender-bending,” or “gender-swapping.” Rule 63 is literally rule number 63 from “Rules of the Internet”: this rule states that manipulation of canon and play are restricted to switching back and forth across the binary of feminine-coded objects, habits, and characters versus masculine-coded objects, habits, and characters.

The rules also suggest that the only sexualities that exist are asexuality and heterosexuality, and attempt to restrict the Internet (and by extension, the realm of cosplaying) to the domain of gender binary-complying people. These rules are transphobic, binary-adhering, and heterocentric in their categorization of gender, sexuality, and cosplay. I called my cosplays of male characters binary-swapping to call attention to this fact; I used binary-swapping to signify the specific kind of change that I made as a cosplayer to source material, instead of implying that I switched between the only two genders that exist.

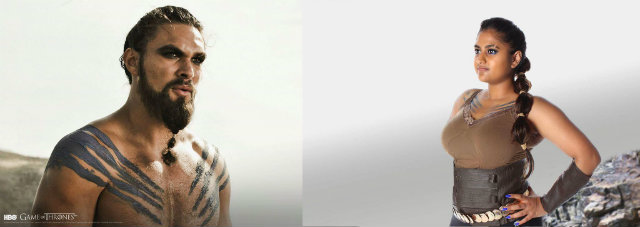

At the onset of my cosplaying, my binary-swapping included a cosplay of Khal Drogo, a character from Game of Thrones. Binding my chest would have made this a crossplay, which is a subgenre of cosplaying where a player emulates a character of a different gender; much like drag, crossplaying is driven by the politics of “passing.” Wearing a shirt instead aligns this with a binary-swap. Wearing a beard, instead of braiding my hair as Drogo’s beard is braided, would have functioned synonymously. I felt that my binary-swap cosplays were cool and great and revolutionary of me. I was content; a baby feminist, exploring the possibility that characters like Khal Drogo could be women who looked like me. This was exciting for me as a cis woman, but as I searched for my community in cosplay—of un-thin femmes of colour—I unlearned the white supremacist ideas that shaped my understanding of cosplay and realized I was limiting myself to cosplaying brown characters because of my brown skin.

I decided to challenge my re-interpretations. I wanted to highlight my racialized features, ethnicity, and identity, rather than making those aspects of myself compliant or limiting myself to brown characters—of which there are very few to choose from, by the way. I coined this “disruptive cosplay.”

As a fan, but also as a fan studies and cosplay researcher, I attended conventions for years before validating the discomfort I experience in cosplay spaces and convention settings or assigning it language. By discomfort, I don’t mean cis-hetero male gaze objectification, but instead the fetishization of my brown skin, the interrogation and attempted invalidating of my identity as a brown-skinned fan. I learned that the searing gaze and ambient unwelcome feeling was informed by the hypervisibility of my brown skin, colonialism, and white supremacy.

Hypervisibility comes into play at the convention because the nearly-homogenous whiteness of both fans and source content suggests that racialized people need not be present at all—unless they’re representing tokenized characters that match their skin tones. Various cosplayers experience this tokenization when they’re referred to as race-first cosplayers. For example, when I cosplayed as Rogue from X-Men, I heard whispers:

“Is that a brown Rogue?”

“Look, a brown Rogue!”

Men (fellow guests and vendors) interrogated my legitimacy as a racialized woman who is a fan, and as a racialized woman who is a cosplayer; they ceaselessly informed me of “missing” components of my cosplay, when I had intentionally combined comic book and screen adaptations of the character. My brown body’s occupation of a white character makes people uncomfortable; it interrupts the white supremacist and cis-patriarchal notion that whiteness and masculinity are universal, while brownness and femininity are other.

How are whiteness and masculinity universal? At cons and in fan communities, protagonists don’t just happen to all be white men. When whiteness and masculinity are the default, or neutral, white men can play whatever character they like, while women of colour like me are expected to stick to playing racialized characters. As such, the con is a site where white universality, white supremacy, is replicated: unsurprising, because this is colonial logic and Canada is a colonial nation state. Colonies are founded and maintained by white cis men who want to demolish Indigenous peoples, institute themselves as people with a natural right to land and bodies, and claim authority over representing the peoples they’re trying to colonize.

White people are very comfortable with the idea of other white people occupying the bodies of people of colour and Indigenous peoples, whether by wearing our regalia or painting their skin so that it looks like ours. Meanwhile, people of colour and Indigenous people who insist on their racialization or their own specific Indigeneity are denied, questioned, and harassed. This happens at the con because colonialism is tied up not only in the establishment of the colony, but also in the ongoing maintenance, expansion, and exploitation of the colony.

Colonialism uses white supremacy to establish colonizers as the purveyors of ultimate authority. That’s what makes them experts, that’s what enables the idea of whiteness as a default, and that’s why I’ve never heard anyone exclaim, “Oh my god, a white Princess Jasmine!” while people of colour can not only play people of colour, they can only play racialized characters of the race that they actually are. We’d still hear “Oh my god, a Korean Princess Jasmine!” (though of course, they wouldn’t say Korean, they’d say Asian).

This colonial imperative guarantees the right of white bodies to access non-white bodies—both by occupying them (like when white people play characters of colour) and by questioning us as a means of continually establishing whiteness as an authority. The way this happens with racialized cosplayers is through interrogating our expertise, questioning our existence, and denying the validity of our work.

I’m a disruptive cosplayer because I want to fight this white supremacy. I want to make space for people who look like me in my fandoms. By the time I cosplayed Daenerys Targaryen, another character from Game of Thrones, I was making conscious decisions to undermine the colonialism of cons: omitting blue contacts, skin lightening makeup, and a blonde wig was my way of taking up space as an Indian woman within popular culture. I created this cosplay consciously as a vehicle for a non-thin, non-white woman to take up space within the Game of Thrones fandom, but also the physical space of the Canadian convention I attended. On my disruptive cosplay journey, I’ve been inspired by other cosplayers and artists of colour, including activist and cartoonist Vishavjit Singh, #28daysofblackcosplay, Kiss a Frog, and Markus Prime Lives. Disruptive cosplay is something I do because it allows me to represent myself, but it also addresses racism in the cosplay community by manipulating canon.

Canadian cons regularly host up to and over 100,000 fans in an enclosed space that is distinctly white. I’ve been attending cons for seven years, and they’re consistently 90 percent white people—and that’s being generous with my estimate of the ranks of people of colour.

There is discomfort involved in the con for me. I compromise my safety in these enclosed spaces; anyone who has ever attended a con (particularly with accessibility needs not met by most physical spaces) knows the challenges and time commitment involved in attempting to exit the space. Not to mention that this space is curated on stolen land.

The white people who occupy the con space look at me like I don’t belong—unless I’m being sexualized because then I belong to them. For me, it’s through cosplay that I can negotiate what I know and love, while imagining what voices, faces, and conversations need to be amplified. Fan activity is a multibillion-dollar industry, and I want to model the kinds of characters I wish I grew up with when I cosplay. I can’t wait to see what kinds of idols the future will hold.

—

ABOUT

Pree Rehal is an MA student in the Communication and Culture program at York and Ryerson Universities. Pree is interested in transgressive play, subcultures, and feminism. Pree researches cosplay, politics of representation, hip hop cultures, Sikhism, fandom, and accessibility. Their MA thesis is on people of colour who engage in steampunk costuming, and their past research includes Disney Princesses, selfies, and subversive cosplay. You can follow them on Twitter @Preezilla.

Update: Pree has come out as non-binary trans and uses they/them pronouns.

“I Fight White Supremacy by Cosplaying” is from our FUTURES issue (spring 2016)